Join us at Transfer 2025 to hear how industry leaders are building payments infrastructure for a real-time world.Register Today →

Single-entry and double-entry accounting are both methods of record-keeping for companies’ financial transaction data. Single-entry accounting records each transaction one single time, while double-entry accounting records each transaction twice, once as a debit and once as a credit.

What is Single-Entry Accounting?

Single-entry accounting (also known as single-entry bookkeeping) is a method of tracking a company’s assets, liabilities, income, and expenses by recording each transaction one single time. As its name suggests, it lists income and expenses in a single row, with positive values for income and negative values for expenses.

What is Double-Entry Accounting?

Double-entry accounting records each of a company’s financial transactions twice, as corresponding debits and credits. With double-entry accounting, every entry to a given account requires a corresponding, opposite entry to a different account. The total of all of the different debit and credit entries must balance out. This method tracks not just cash on hand, but also the value of all of a company’s assets.

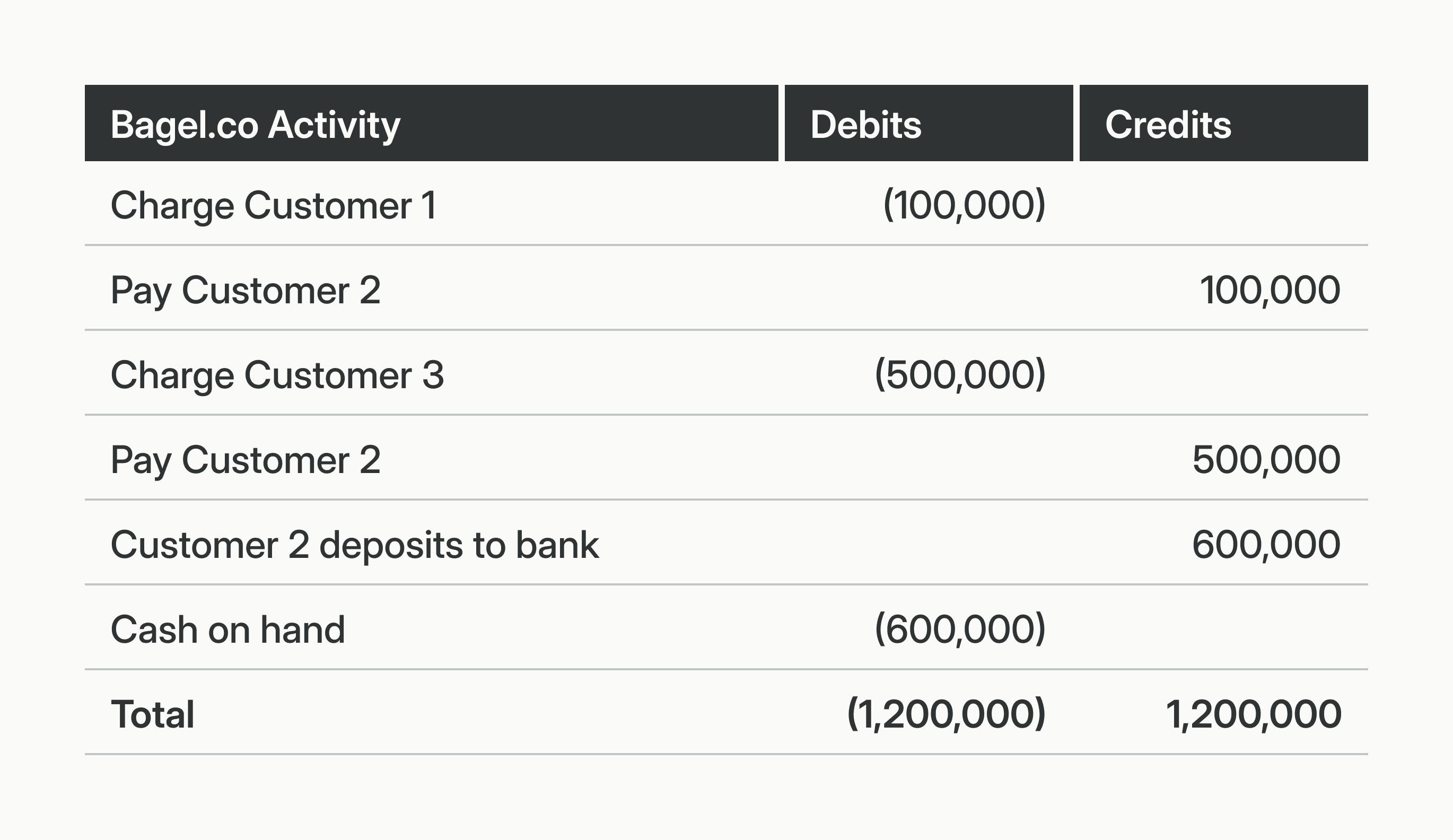

As an example, let’s say you run Bagel.co, a company that allows users to buy, sell, and trade bagels. Bagel.co moves funds between accounts that they operate on behalf of their customers. Customers 1-3 buy and sell bagels to each other, and cash out the balances of their accounts on your platform to external banks. Below is an example double-entry ledger of their transactions.

Remembering Assets - Liabilities = Equity is the key to double-entry accounting.

What is the difference between Single-Entry Accounting and Double-Entry Accounting?

When a business sells a good using single-entry accounting, the expenses for the good are recorded when the business purchases the good and the revenue is recorded when the business sells the good.

Here, let's imagine running a bagel shop. If our bagel shop uses single-entry accounting, we record the expense of buying flour and salt separately from recording the revenue of a sold bagel. While this is a feasible option for a small business, one thing to keep in mind is that single-entry accounting can be error-prone. There are no credit and debit totals to match, so single-entry doesn’t allow for double-checking the accuracy of the bookkeeping. For example, if the bagel shop forgets to record a sale or an expense, their balances won’t match.

Alternatively, if a business is using double-entry accounting, when the business purchases goods they record an increase in inventory along with a decrease in assets at the same time and within the same transaction.

Here, imagine our bagel shop buys salt and flour in cash. We record the purchase of flour and salt along with a decrease in cash assets. When we sell a bagel, we record a decrease in bagel inventory and an increase in cash assets (the revenue from the sold bagel).

Single-entry accounting is only practical for smaller businesses with low transaction volumes, as it fails to take concepts like inventory into account. A business also can not use single-entry accounting to create certain necessary financial documents, like balance sheets.

For businesses that move money as part of their core business, like marketplaces, it is recommended that they use double-entry accounting. Not only does it enable accurate calculations and simplify the preparation of financial statements, it also helps to reduce the risk of errors or fraud. Double-entry accounting is required under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

To learn more about this topic, check out these additional resources:

Try Modern Treasury

See how smooth payment operations can be.

Learn

Ledgers are foundational to any company that moves money at scale. Explore the accounting fundamentals behind the ledgering process, the differences between application ledgers and general ledgers, and more.

A chart of accounts (COA) is an index of all the different accounts within a company’s ledger.

A digital wallet (also sometimes called an electronic wallet) is an application that securely stores digital payment information and password data for a user.

A Ledger Database is a database that stores accounting data. More specifically, a ledger database can store the current and historical value of a company’s financial data.

Learn the difference between Single-Entry Accounting and Double-Entry Accounting

Data immutability is the idea that information within a database cannot be deleted or changed. In immutable—or append-only—databases, data can only ever be added.

In the context of software, concurrency control is the ability for different parts of a program or algorithm to complete simultaneously without conflict. Concurrency controls in a database ensure that simultaneous transactions will be parsed appropriately.

An API call is idempotent if it has the same result, regardless of how many times it is applied. Inadvertent duplicate API calls can cause unintended consequences for a business, idempotency helps provide protection against that.

A ledger API allows companies who need to move money at scale quickly and easily access, track, audit, and unify all of their financial data in one place.

The ledger balance, also called the current balance, is the opening amount of money in any checking account every morning. The ledger balance should remain the same for the duration of the day.

A ledger (also called a general ledger, accounting ledger, or financial ledger) is a record-keeping system for a company’s financial transaction data.

A subsidiary ledger is used to keep track of the details for a specific control account within a company’s general ledger.